I apply my advanced training and research in complexity science, biology, history, and philosophy to the design and analysis of distributed software systems from a socio-technical perspective.

Named Entity Recognition is the problem of locating and categorizing chunks of text that refer to…well…entities. “Entities” usually means things like people, places, organizations, or organisms, but can also include things like currency, recipe ingredients, or any other class of concepts to which a text might refer. NER has a wide range of applications in text mining. Recently, for example, I worked with researchers at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science to extract names of people from meeting minutes in their instutional archives, in order to identify patterns of cooperation in committees and subcommittees. I frequently use NER to identify organisms mentioned in scientific publications.

The first step in NER is typically to train a model that can predict categories (e.g people, places) for words or phrases. The Stanford Natural Language Processing Group provides a wonderfully robust set of tools for this. They also provide a few classification models that are already trained. In this post I’ll describe how to use one of their pre-trained models to perform NER on a large collection of texts, using Python.

Before you start

Stanford NER

You’ll need to download the Stanford NER package, and unpack it somewhere. I put it directly in my home directory, so the full path is:

/Users/erickpeirson/stanford-ner-2015-04-20

The contents should look something like this:

build.xml

classifiers

lib

LICENSE.txt

ner-gui.bat

ner-gui.command

ner-gui.sh

ner.bat

ner.sh

NERDemo.java

README.txt

sample-conll-file.txt

sample-w-time.txt

sample.ner.txt

sample.txt

stanford-ner-3.5.2-javadoc.jar

stanford-ner-3.5.2-sources.jar

stanford-ner-3.5.2.jar

stanford-ner.jar

Java JDK

For Stanford’s NER tool to work, you’ll need to have the Java Development Kit installed. You can get the latest version from this page.

PyNER

You’ll also need to install PyNER, which provides a Python interface for the Stanford NER. You can either download it from the link above, or directly from PyPI:

1

pip install -U ner

NOTE: As of this writing, the most recent version of PyNER has a bug that causes rampant socket timeouts. This is fixed in this fork, and a pull request has been submitted to patch the main fork. If you run into this problem, you may want to:

- Download PyNER from here (look for the “Download ZIP” button at lower right).

- Unzip the downloaded file (

pyner-master.zip)somewhere. - Install via

pip:

1

2

3

pip uninstall pyner

cd /path/to/pyner-master

pip install ./

One text at a time

The simplest use-case for the Stanford NER is to tag a single text file. I scraped the text from the Wikipedia entry for Carl Linnaeus, and saved it as linnaeus.txt in my home directory.

Here’s a sampling from the text:

When Carl was born, he was named Carl Linnæus, with his father’s family name. The son also always spelled it with the æ ligature, both in handwritten documents and in publications.[9]Carl’s patronymic would have been Nilsson, as in Carl Nilsson Linnæus. One of a long line of peasants and priests, Nils was an amateurbotanist, aLutheranminister, and thecurateof the small village of Stenbrohult in Småland. Christina was the daughter of therectorof Stenbrohult, Samuel Brodersonius.

We can tag this text file using:

1

~/stanford-ner-2015-04-20/ner.sh ~/linnaeus.txt > ~/linnaeus_tagged.txt

The > operator directs the output to a new file, linnaeus_tagged.txt. Here’s the chunk from this file that corresponds to the passage that I pulled out, above:

When/O Carl/PERSON was/O born/O ,/O he/O was/O named/O Carl/PERSON Linnæus/PERSON ,/O with/O his/O father/O ‘s/O family/O name/O ./O The/O son/O also/O always/O spelled/O it/O with/O the/O æ/O ligature/O ,/O both/O in/O handwritten/O documents/O and/O in/O publications/O ./O -LSB-/O 9/O -RSB-/O Carl/PERSON ‘s/O patronymic/O would/O have/O been/O Nilsson/PERSON ,/O as/O in/O Carl/PERSON Nilsson/PERSON Linnæus/PERSON ./O One/O of/O a/O long/O line/O of/O peasants/O and/O priests/O ,/O Nils/PERSON was/O an/O amateurbotanist/O ,/O aLutheranminister/O ,/O and/O thecurateof/O the/O small/O village/O of/O Stenbrohult/LOCATION in/O Småland/LOCATION ./O Christina/PERSON was/O the/O daughter/O of/O therectorof/O Stenbrohult/O ,/O Samuel/PERSON Brodersonius/PERSON ./O

Note that this is the same text, with two notable differences:

- Each word has a tag after it, e.g.

/Oor/PERSON, which indicates the class to which that token (word) belongs. - Some special characters have been converted to string representations. For example, the left square bracket,

[is converted to-LSB-.

Just looking at this passage, it looks like the Stanford NER did a fairly good job of recognizing instances of the PERSON and LOCATION class. Nice.

Running in server mode

Since most of my text mining work takes place in a Python environment, I’d really like to be able to perform NER without shuffling text files around and making BASH calls. Luckily, the folks at Stanford provided mechanisms to accomplish this fairly easily.

We need to do two things:

- Run the Stanford NER in server mode.

- Use a Python package called PyNER to call the NER server from a Python script.

To start the server, I followed the instructions on the Stanford NLP website, except that I increased the memory allocation to 1000MB (that’s the -mx1000m bit on line 4).

1

2

3

4

cd ~/stanford-ner-2014-10-26

cp stanford-ner.jar stanford-ner-with-classifier.jar

jar -uf stanford-ner-with-classifier.jar classifiers/english.all.3class.distsim.crf.ser.gz

java -mx1000m -cp stanford-ner-with-classifier.jar edu.stanford.nlp.ie.NERServer -port 9192 -loadClassifier classifiers/english.all.3class.distsim.crf.ser.gz &

Here I’m using the 3-class English language classifier (english.all.3class.distsim.crf.ser.gz) provided with the Stanford NER package. There are a few others in the classifiers subdirectory, and you can download more from this page. For German-language NER I’ve used the DeWac classifier with great success.

The & bit at the end of line 4 tells BASH to run the server in the background, so you should see a PID, then a start-up message from the server, and then back to your command prompt (you may need to press enter).

1

2

[1] 14841

Loading classifier from classifiers/english.all.3class.distsim.crf.ser.gz ... done [3.9 sec].

And that’s it! The server should be running on port 9192. If you direct your browser to http://127.0.0.1:9192, you should see something like this:

GET/O //O HTTP/1/O .1/O

Configuring PyNER

PyNER provides a Python module called ner, which contains a few different classes for interacting with Stanford NER.

First, import ner just like you’d expect:

1

import ner

We can then spin up a new tagger with:

1

tagger = ner.SocketNER(host='localhost', port=9192, output_format='slashTags')

This tells PyNER that our server is running locally on port 9192, and to return results in the “slashTags” format – just like we saw when we ran the NER from the command-line. SocketNER is supposed to support other output formats, including an XML format, but so far I haven’t gotten them to work properly. Maybe you’ll have better luck.

Suppose that I have a string containing some of the text above:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

someText = """When Carl was born, he was named Carl Linnæus, with his father's family name.

The son also always spelled it with the æ ligature, both in handwritten

documents and in publications.[9]Carl's patronymic would have been Nilsson,

as in Carl Nilsson Linnæus.

One of a long line of peasants and priests, Nils was an amateurbotanist,

aLutheranminister, and thecurateof the small village of Stenbrohult in Småland.

Christina was the daughter of therectorof Stenbrohult, Samuel Brodersonius."""

Now we can pass chunks of text to the NER server using the SocketNER’s tag_text method. What we get back is a lot like what we saw on the command line.

1

tagger.tag_text(someText)

u"When/O Carl/PERSON was/O born/O ,/O he/O was/O named/O Carl/PERSON Linn\xe6us/PERSON ,/O with/O his/O father/O 's/O family/O name/O ./O \nThe/O son/O also/O always/O spelled/O it/O with/O the/O \xe6/O ligature/O ,/O both/O in/O handwritten/O documents/O and/O in/O publications/O ./O \n-LSB-/O 9/O -RSB-/O Carl/PERSON 's/O patronymic/O would/O have/O been/O Nilsson/PERSON ,/O as/O in/O Carl/PERSON Nilsson/PERSON Linn\xe6us/PERSON ./O \nOne/O of/O a/O long/O line/O of/O peasants/O and/O priests/O ,/O Nils/PERSON was/O an/O amateurbotanist/O ,/O aLutheranminister/O ,/O and/O thecurateof/O the/O small/O village/O of/O Stenbrohult/LOCATION in/O Sm\xe5land/LOCATION ./O \nChristina/PERSON was/O the/O daughter/O of/O therectorof/O Stenbrohult/O ,/O Samuel/PERSON Brodersonius/PERSON ./O \n"Parsing NER tags

The raw NER output above isn’t very useful in its present form. We need to parse the tags in a way that will yield useful data about our text. The way that you choose to go about this will be influenced by what exactly you want to do with the data. In this case, I want to do two things:

- Pull out all of the names of entities (e.g. people and locations) in the text, and

- Count the number of people and location instances in the text.

On a quick visual inspection of the tagged text output, we can see that individual tokens are delimited by whitespace, and tokens (e.g. Carl) and their tags (e.g. PERSON) are separated by the slash / character. We can use the string’s split method along with a simple list-comprehension to start pulling the tagged text apart.

1

2

tagged_tokens = [ tuple(ttok.split('/')) for ttok in tagged_text.split() ]

print tagged_tokens

[(u'When', u'O'), (u'Carl', u'PERSON'), (u'was', u'O'), (u'born', u'O'), (u',', u'O'), (u'he', u'O'), (u'was', u'O'), (u'named', u'O'), (u'Carl', u'PERSON'), (u'Linn\xe6us', u'PERSON'), (u',', u'O'), (u'with', u'O'), (u'his', u'O'), (u'father', u'O'), (u"'s", u'O'), (u'family', u'O'), (u'name', u'O'), (u'.', u'O'), (u'The', u'O'), (u'son', u'O'), (u'also', u'O'), (u'always', u'O'), (u'spelled', u'O'), (u'it', u'O'), (u'with', u'O'), (u'the', u'O'), (u'\xe6', u'O'), (u'ligature', u'O'), (u',', u'O'), (u'both', u'O'), (u'in', u'O'), (u'handwritten', u'O'), (u'documents', u'O'), (u'and', u'O'), (u'in', u'O'), (u'publications', u'O'), (u'.', u'O'), (u'-LSB-', u'O'), (u'9', u'O'), (u'-RSB-', u'O'), (u'Carl', u'PERSON'), (u"'s", u'O'), (u'patronymic', u'O'), (u'would', u'O'), (u'have', u'O'), (u'been', u'O'), (u'Nilsson', u'PERSON'), (u',', u'O'), (u'as', u'O'), (u'in', u'O'), (u'Carl', u'PERSON'), (u'Nilsson', u'PERSON'), (u'Linn\xe6us', u'PERSON'), (u'.', u'O'), (u'One', u'O'), (u'of', u'O'), (u'a', u'O'), (u'long', u'O'), (u'line', u'O'), (u'of', u'O'), (u'peasants', u'O'), (u'and', u'O'), (u'priests', u'O'), (u',', u'O'), (u'Nils', u'PERSON'), (u'was', u'O'), (u'an', u'O'), (u'amateurbotanist', u'O'), (u',', u'O'), (u'aLutheranminister', u'O'), (u',', u'O'), (u'and', u'O'), (u'thecurateof', u'O'), (u'the', u'O'), (u'small', u'O'), (u'village', u'O'), (u'of', u'O'), (u'Stenbrohult', u'LOCATION'), (u'in', u'O'), (u'Sm\xe5land', u'LOCATION'), (u'.', u'O'), (u'Christina', u'PERSON'), (u'was', u'O'), (u'the', u'O'), (u'daughter', u'O'), (u'of', u'O'), (u'therectorof', u'O'), (u'Stenbrohult', u'O'), (u',', u'O'), (u'Samuel', u'PERSON'), (u'Brodersonius', u'PERSON'), (u'.', u'O')]Now we have a list of tuples, where each tuple contains a token (e.g. When) and its tag (e.g. O).

Our next challenge is to figure out which tokens belong together as part of the same “named entity.” For example, notice that in the first sentence Carl and Linn\xe6us occur sequentially, and (to a human reader) are clearly part of the same name (Carl Linn\xe6us), but Stanford’s NER has given each of the terms its own PERSON tag. So we have: [... (u'Carl', u'PERSON'), (u'Linn\xe6us', u'PERSON') ...].

Since Stanford’s NER treats punctuation characters as separate tokens (e.g. ./O), we can be reasonably sure that when a sequence of tokens with the same tag occur together, they probably belong to the same named entity.

In the code below, I generate a list of entities from a single tagged text. Take a look at the comments in the code for cues about what’s going on.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

entities = [] # Named entity instances will go here.

current_entity = [] # Tokens that are part of the current entity will go here.

last_tag = None # We'll use this to check whether a token is part of the same entity as the previous.

for i in xrange(len(tagged_tokens)): # Evaluate each token, in order.

# Separate the token from its tag, so that we can evaluate them separately.

token, tag = tagged_tokens[i]

if tag == 'O' or last_tag != tag: # We've reached the end of the current entity.

# If that entity had a real tag (not 'O' or None), then save it.

if last_tag != 'O' and last_tag != None:

# We save the list of tokens in this named entity, along with its tag, as a tuple.

# string.join() converts the list of tokens into a string.

entities.append((' '.join(current_entity), last_tag))

current_entity = [] # Reset for a new entity.

last_tag = tag # Keep track of the current entity tag; see lines 10 and 12.

current_entity.append(token)

Now we have a list of tuples, each containing a named entity and its corresponding tags.

1

entities

[(u'Carl', u'PERSON'),

(u'Carl Linn\xe6us', u'PERSON'),

(u'Carl', u'PERSON'),

(u'Nilsson', u'PERSON'),

(u'Carl Nilsson Linn\xe6us', u'PERSON'),

(u'Nils', u'PERSON'),

(u'Stenbrohult', u'LOCATION'),

(u'Sm\xe5land', u'LOCATION'),

(u'Christina', u'PERSON'),

(u'Samuel Brodersonius', u'PERSON')]Now that we have our entities and their classes (tags), we can go in many different directions. My first objective in this example was to pull out all of the entities and group them by class. In the code below, I iterate over the list of (entity,tag) tuples, and sort the entities into a dictionary (entities_binned) based on their tags.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

entities_binned = {}

for entity, tag in entities:

# When we encounter a tag for the first time, we need to create a spot for it

# in our dictionary.

if tag not in entities_binned:

entities_binned[tag] = []

entities_binned[tag].append(entity)

This yields a dictionary with classes (tags) as keys, and lists of entities as values.

1

entities_binned

{u'LOCATION': [u'Stenbrohult', u'Sm\xe5land'],

u'PERSON': [u'Carl',

u'Carl Linn\xe6us',

u'Carl',

u'Nilsson',

u'Carl Nilsson Linn\xe6us',

u'Nils',

u'Christina',

u'Samuel Brodersonius']}I’m also interested in the total number of entities for each class in this text. There are several ways to do this. One simple approach is to use a Counter from the collections module.

First, we need to pull out the list of tags from our list of entities. Python’s built-in zip function is handy for this. We can unzip (using the * operator) our list of entity,tag tuples into two lists: one containing entities, the other containing tags.

1

2

entity_list, tag_list = zip(*entities) # `*` causes zip() to *unzip* the list of tuples.

tag_list

(u'PERSON',

u'PERSON',

u'PERSON',

u'PERSON',

u'PERSON',

u'PERSON',

u'LOCATION',

u'LOCATION',

u'PERSON',

u'PERSON')We can import the Counter class directly from the collections module.

1

from collections import Counter

Counter takes a list of hashable objects, and returns a dictionary-like object with unique objects (in this case, tag strings) as keys, and counts as values.

1

2

tag_counts = Counter(tag_list)

tag_counts

Counter({u'PERSON': 8, u'LOCATION': 2})Painless! You’ll likely want to develop your own procedures, depending on what question you’re trying to address. But the examples above should give you a place to start.

Spoiler

Now that you’ve gone to the trouble of parsing the tagged text output, it turns out that ner already has much of that functionality built in. The get_entities method will return a dictionary similar to the one that we generated above (entities_binned).

1

tagger.get_entities(someText)

{u'LOCATION': [u'Stenbrohult', u'Sm\xe5land'],

u'O': [u'When',

u'was born , he was named',

u", with his father 's family name . The son also always spelled it with the \xe6 ligature , both in handwritten documents and in publications . -LSB- 9 -RSB-",

u"'s patronymic would have been",

u', as in',

u'. One of a long line of peasants and priests ,',

u'was an amateurbotanist , aLutheranminister , and thecurateof the small village of',

u'in',

u'.',

u'was the daughter of therectorof Stenbrohult ,',

u'.'],

u'PERSON': [u'Carl',

u'Carl Linn\xe6us',

u'Carl',

u'Nilsson',

u'Carl Nilsson Linn\xe6us',

u'Nils',

u'Christina',

u'Samuel Brodersonius']}Note that the untagged chunks of texts are also returned under 'O'. Personally, I prefer to parse the tagged text myself.

Scaling up

What we’ve done so far has dealt with a single text. Since we’d like to scale up to working with many texts, we should define some functions for re-use. The following three functions capture the procedures that we’ve developed so far. They’re not quite as concise as they could be, but I’ll leave them as written to make it easier to follow.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

def parse_tags(tagged_text):

"""

Parse the output of :meth:`ner.SocketNER.tag_text` .

Parameters

----------

tagged_text : str

Expected to be in the "slashTags" format.

Return

------

entities : list

A list of (entity,tag) tuples, in the order that they occur in the tagged text.

"""

tagged_tokens = [ tuple(ttok.split('/')) for ttok in tagged_text.split() ]

entities = [] # Named entity instances will go here.

current_entity = [] # Tokens that are part of the current entity will go here.

last_tag = None # We'll use this to check whether a token is part of the same entity as the previous.

for i in xrange(len(tagged_tokens)): # Evaluate each token, in order.

# Separate the token from its tag, so that we can evaluate them separately.

token, tag = tagged_tokens[i]

if tag == 'O' or last_tag != tag: # We've reached the end of the current entity.

# If that entity had a real tag (not 'O' or None), then save it.

if last_tag != 'O' and last_tag != None:

# We save the list of tokens in this named entity, along with its tag, as a tuple.

# string.join() converts the list of tokens into a string.

entities.append((' '.join(current_entity), last_tag))

current_entity = [] # Reset for a new entity.

last_tag = tag # Keep track of the current entity tag; see lines 10 and 12.

current_entity.append(token)

return entities

def sort_entities(entities):

"""

Sort entities into bins based on their tags.

Parameters

----------

entities : list

A list of (entity,tag) tuples. See :func:`.parse_tags` .

Returns

-------

entities_binned : dict

Keys are tags/classes, values are lists of entities.

"""

entities_binned = {}

for entity, tag in entities:

# When we encounter a tag for the first time, we need to create a spot for it

# in our dictionary.

if tag not in entities_binned:

entities_binned[tag] = []

entities_binned[tag].append(entity)

def count_tags(entities):

"""

Count the number of entities for each tag.

Parameters

----------

entities : list

A list of (entity,tag) tuples. See :func:`.parse_tags` .

Returns

-------

tag_counts : :class:`collections.Counter`

Keys are tags/classes, values are the number of entities for each respective tag.

"""

entity_list, tag_list = zip(*entities) # `*` causes zip() to *unzip* the list of tuples.

tag_counts = Counter(tag_list)

return tag_counts

Now we need some texts.

At the moment I’m working on a project involving a moderate collection of texts from a prominent history of science journal, provided by JSTOR. They’re in XML format, so I use ElementTree to parse the content and pull out text. Obviously your procedure for loading texts will depend on how you’ve stored your text collection, so I won’t dwell on the specifics.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

import os

import xml.etree.ElementTree as ET

jpath = '/path/to/my/data'

texts = []

for dname in os.listdir(jpath):

if not dname.startswith('.'):

with open(os.path.join(jpath, dname), 'r') as f:

e = ET.fromstring(f.read())

texts.append(' '.join([page.text for page in e.findall('.//page') ]))

The important thing is that I now have a list of texts (texts). Each element of the list is a single string containing the text of an entire document. If I wanted to perform NER on a finer scale, I might have chunked those documents up by page, paragraph, or even sentence.

Now we can perform NER on each of the texts, and store the parsed entities.

1

2

3

4

5

entities_in_text = []

for text in texts:

tagged_text = tagger.tag_text(text)

entitites = parse_tags(tagged_text)

entities_in_text.append(entities)

Note: This may take a while, depending on the size of your collection. When I ran this on a collection of ~2000 article-length texts on my iMac (3.4 GHz i7), it took about 30 minutes. Java never really sucks up more than about 40% of one core (Python uses a negligble amount), which leads me to believe that there are some pretty big inefficiences in passing data to and from the socket server. It may be worth exploring other approaches. One thought would be to run multiple NER socket servers, and customizer PyNER to distribute and monitor tasks using select. If you’re already working with a collection of text files on disk, it might also make sense to use subprocess to call NER via command-line (bypass PyNER and the socket server altogether), but that’s a bit outside the scope of this post.

If all goes well, entities_in_text should be a list with the same shape (read: the same length) as texts.

1

len(texts), len(entities_in_text)

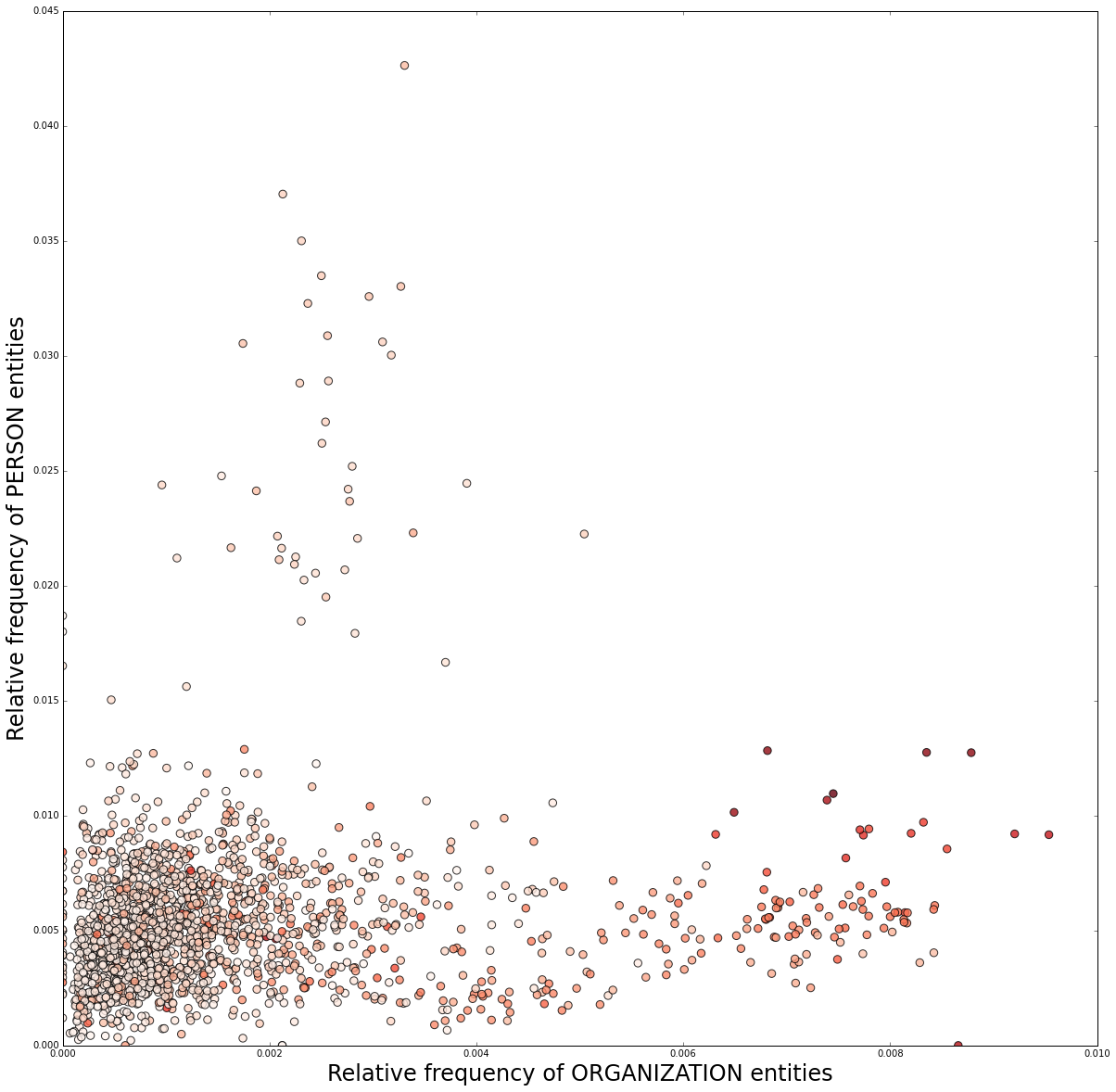

(1917, 1917)Where you go from here really depends on your research questions. Just to get a sense of the texture of this text collection, I tried plotting the relative frequencies of the three tags in this NER model ('PERSON', 'LOCATION', 'ORGANIZATION').

First, I pulled out the tag counts for each text.

1

counts = [ count_tags(e) for e in entities_in_text ]

Then I pulled out the counts for each tag. I normalized the counts for each text by the length of that text; see line 6, below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

i = 0

counts_divided = {'PERSON':[], 'LOCATION':[], 'ORGANIZATION':[]}

for c in counts:

for k in counts_divided.keys():

if k in c:

counts_divided[k].append(float(c[k])/len(texts[i]))

else:

counts_divided[k].append(0.)

i += 1

# Casting these to Numpy arrays can help if we want to transform the data later.

location = np.array(counts_divided['LOCATION'])

organization = np.array(counts_divided['ORGANIZATION'])

person = np.array(counts_divided['PERSON'])

MatPlotLib makes it easy to generate beautiful plots. In this case I made a simple scatterplot.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.cm as cm

plt.figure(figsize=(10,10)) # Makes a 10in x 10in.

# Color nodes by frequency of LOCATION entities (redder => more).

cvalues = [ cm.Reds(c) for c in list((location - location.min())/location.max())]

# Scatter plot.

plt.scatter(organization, person, c=cvalues, s=30, alpha=0.8, lw=1)

plt.ylim(0.,0.045)

plt.xlim(0.,0.01)

# Axis labels.

plt.xlabel('Relative frequency of ORGANIZATION entities', fontsize=16)

plt.ylabel('Relative frequency of PERSON entities', fontsize=16)

plt.show()

The degree of “redness” indicates the relative frequency of LOCATION entities.

This view of the corpus shows some interesting patterns. Recall that this corpus is comprised of ~2,000 texts from a prominent journal focusing on the history of science. Most of the texts are concentrated in a big cluster in the lower left. But there is also a more diffuse cloud of texts with a higher-than-usual representation of PERSON tags. Interestingly, none of those texts have a particularly high frequency of LOCATION or ORGANIZATION entities. Those texts may reflect a much more person-centric narrative style, or they may be due to excessive name-dropping of other scholars (see below).

There is a second “arm” that extends along the X-axis; those texts have high frequencies of both ORGANIZATION and LOCATION entities (dark red points). Those texts may be institutional histories.

Next Steps

For most projects, this kind of unsupervised tagging will be just a first, crude step. There are several problems that one may wish to address before trying to interpret the results of this procedure.

-

Disambiguation. The tagged “entities” that we get back from the NER model are still just strings of text. We don’t know to whom those entity-tokens refer, nor which of the entity-tokens in a given text might refer to the same person. In the sample text about Linnaeus that we used above, for example, we have at least four different PERSON entity-tokens that probably refer to the same person:

'Carl','Carl Linn\xe6us','Carl','Carl Nilsson Linn\xe6us'. -

Filtering. Not all of the tagged entities in these texts will be relevant for our research questions. In the example above, many of the PERSON entities are probably either in-text citations (e.g.

(Joe Bloggs, 1992)), or mentions of other historians in footnotes (e.g.According to Fred Historian, the wigidere is on the mantifore...). Since I’m interested only in the entity-tags corresponding to historical actors (the people about which the historians are writing), these are false-positives.

In future posts I’ll address each of those issues in the context of a few ongoing text-analysis projects.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.